Measuring Semantic Coherence of a Conversation ISWC 2018

Preprint: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1806.06411.pdf

Code: https://github.com/svakulenk0/semantic_coherence

Slides: https://github.com/svakulenk0/svakulenk0.github.io/blob/master/pdfs/slides/iswc18.pdf

Video: http://videolectures.net/iswc2018_vakulenko_measuring_coherence_conversatio/

Imagine: you sit in a train, in which many different conversations are going on at the same time. A couple next to the window is planning their honey-moon trip; the girls at the table are discussing their homework; a granny is in a call with her great-grandson. You close your eyes and try to recover who is talking to whom by paying attention to the content of the conversations and not to the origin of the sound waves:

- Mhm .. and then we add the two numbers from the Pythagoras’ equation?

- … but I am not quite sure about that hotel you booked on-line… Don’t you think we should stick with the one we found on Airbnb?

- All right, sweetheart, kiss your mum for me! I will be back before the Disney movie starts, I promise.

- I think it is the one we did on the blackboard on Monday or was it the one with Euclidean distance?

- For me both options are really fine as long as it is on Bali.

It is relatively easy to tell the three conversations apart. We hypothesize that this is due to certain semantic relations between utterances from the same dialogue that make it meaningful, or coherent, which brought us to the following set of questions:

- What are the relations between the words in a dialogue (or rather the concepts they represent) that make a dialogue semantically coherent, i.e. making sense? and

- Can we use available knowledge resources (e.g. a knowledge graph) to tell whether a dialogue makes sense?

The later is particularly important for dialogue systems that need to correctly interpret the dialogue context and produce meaningful responses.

To study these two questions we cast the semantic coherence measurement task as a classification problem. The objective is to learn to distinguish real (mostly coherent) dialogues from artificially generated dialogues, which were made incoherent by design. Intuitively, the classifier is trained to assign a higher score to the coherent dialogues and a lower score to the incoherent (corrupted) dialogues, so that the output score reflects the degree of coherence in the dialogue.

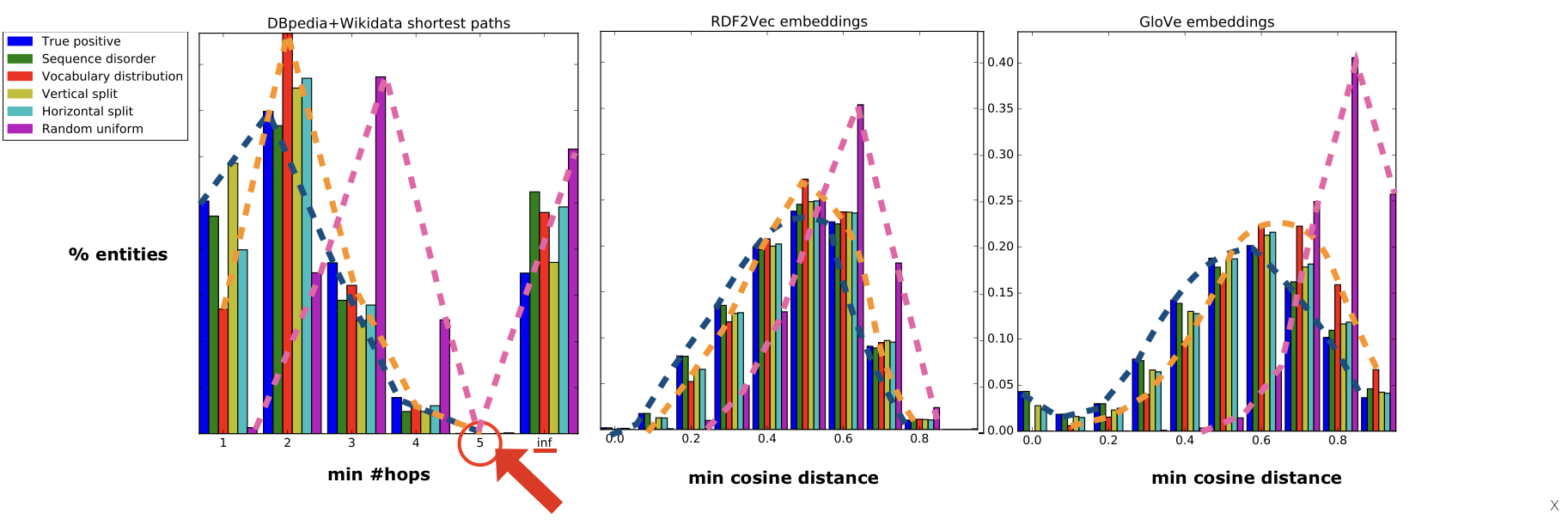

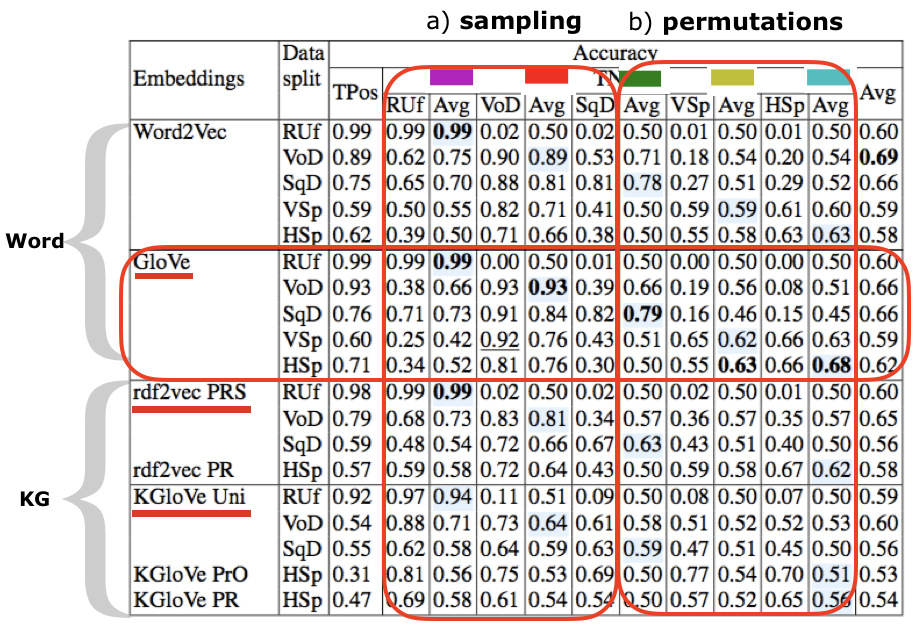

We extended the Ubuntu Dialogue Corpus, which is a large dialogue dataset containing almost 2M dialogues extracted from IRC (public chat) logs, with generated negative samples to provide an evaluation benchmark for the coherence measurement task. We came up with 5 different ways to generate negative samples, i.e. incoherent dialogues by a) sampling the vocabulary (1. uniformly at random; 2. according to the corpus-specific distribution) and b) permutations of the original dialogues (3. shuffling the sequence of entities, or combining two different dialogues via 4. horizontal and 5. vertical splits).

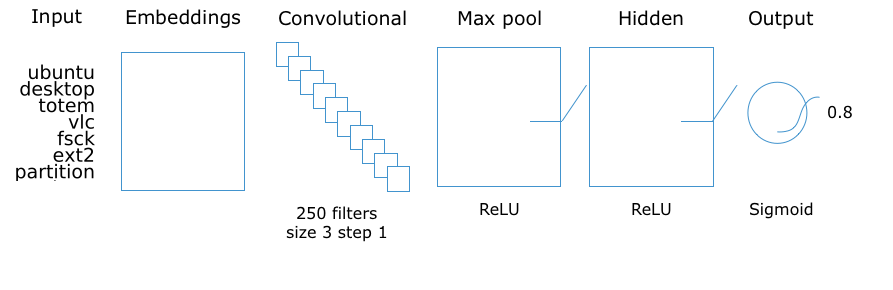

We also implement and evaluate three different approaches on this benchmark. Two of them are based on a neural network classifier (Convolutional Neural Network) using word or, alternatively, Knowledge Graph embeddings; and the third approach is using the original Knowledge Graph (Wikidata+DBpedia converted to HDT) to induce a semantic subgraph representation for each of the dialogues.

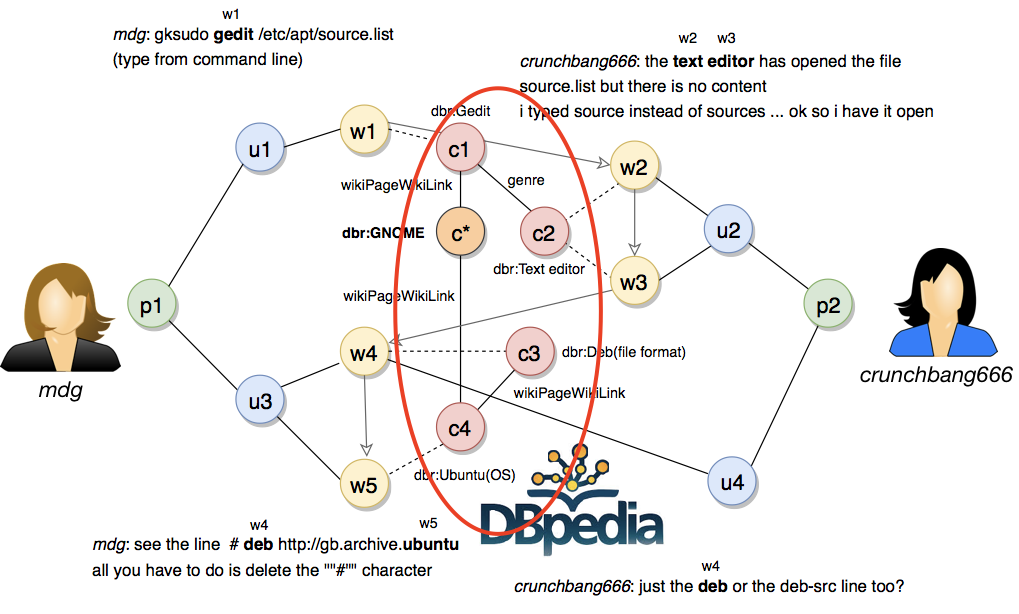

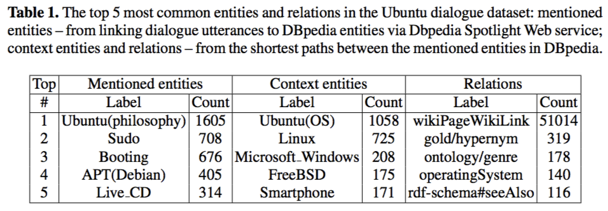

In order to align dialogues with the Knowledge Graph we perform entity recognition using the DBpedia Spotlight API. Thus, each dialogue is represented as a sequence of DBpedia entities. We perform bidirectional top-k shortest path search (k=5) for each of the entities with respect to the set of entities previously mentioned in the same conversation. This way the dialogues include not only the entities explicitly mentioned in the conversation but also the ones that remain implicit but are tightly related to the mentioned entities since they are located on the intersection between them. These entities constitute, in some sense, a semantic context (or background) in which the conversation evolves and revolves around:

There are a few problems with this approach, however. The top-k algorithm runs out of memory after 4 hops since the dialogue subgraph grows way too big. Also, there is no straight-forward way to classify the produced subgraphs. One obvious feature, for example, is the distance between the entities in the subgraph.

As an alternative approach, instead of crawling the original Knowledge Graph every time and feature-engineering on the induced subgraphs, we can use the pre-trained entity embeddings (e.g. RDF2Vec and KGlove embeddings), which compress the relations into a single vector per entity. The pre-trained entity embeddings can be applied after the input layer of a neural network to integrate the relations from the background knowledge and can be substituted (compared) with the word embeddings using the same architecture:

Results

Good news: the Knowledge Graph embeddings adequately reflect the entity relations and help to overcome the performance bottleneck of the graph-crawling approach. Bad news for the Knowledge Graph though is that the relations it encodes were not sufficient to distinguish incoherent conversations and the knowledge model based on word embeddings, i.e. encoding the word co-occurrences in text, consistently achieves better performance across all types of incoherence examples.

In general, it is easy to separate real conversations from random entity sequences (Accuracy: 0.99 for random uniform sampling) also using the Knowledge Graph embeddings, and the sequence permutation task remains challenging for all knowledge models including word embeddings (maximum Accuracy: 0.68 for horizontal and 0.63 for vertical splits).

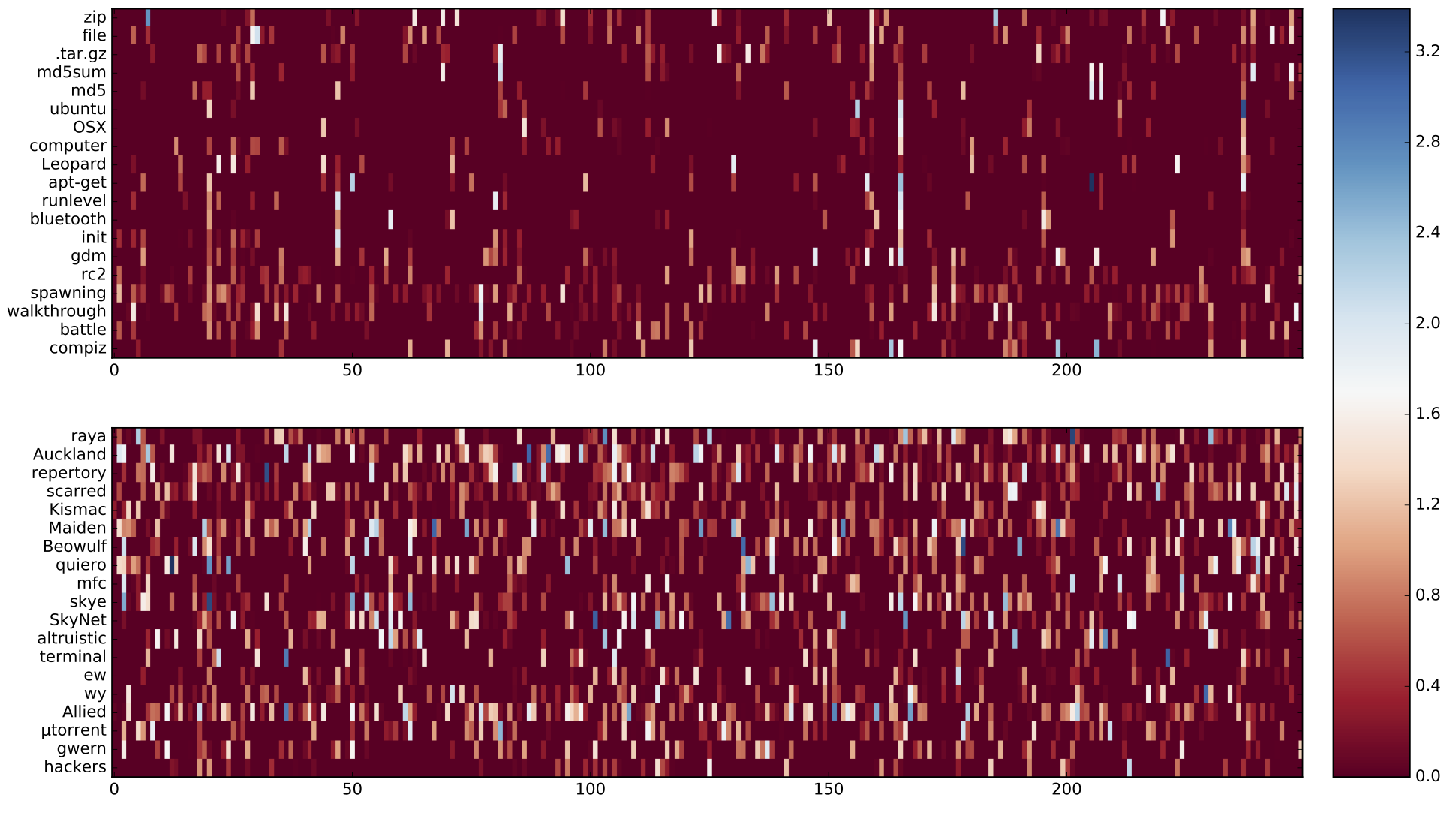

Visualization of the embeddings layer activation demonstrates the point of view of the neural network processing the input sequences. We interpret the vertical bars, which indicate the high activation weights, stretching across the conversation as semantic coherence patterns, which help the neural network to assign a higher coherence score for positive examples, as opposed to the “white noise” pattern from the random entity sets:

This interpretation supports also the activation patterns observed in the horizontal split samples, where two different dialogues were concatenated in order to introduce an explicit coherence break. The vertical bars continuous in the same dimension from the top to the bottom (positive example at the top) are interrupted because of the topic switch (true negative example, bottom):

Discussion

One reason for the poor performance of the knowledge graph embeddings can be the errors propagating from the entity linking step. The subgraph induction approach can recover from such errors since it has access to the original graph. For example, when Ubuntu is erroneously disambiguated to reference the philosophy, instead of the operating system, the original meaning is restored from the context of the conversation since many other entities are linked to it:

Word embeddings do not have this issue since they hold all meanings in the same vector (there is only one vector for each surface form). It is clear that there is a need for an analogous solution for entity linking from natural language to the Knowledge Graph, able to model the probability distribution and back-propagate the error, i.e. entity linking should be implemented in an end-to-end rather than a pipeline manner.

Reference

Svitlana Vakulenko, Maarten de Rijke, Michael Cochez, Vadim Savenkov, and Axel Polleres. Measuring semantic coherence of a conversation. In Proceedings of the 17th International Semantic Web Conference (ISWC 2018), Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS), Monterey, CA, October 2018. Springer.

@inproceedings{Vakulenko2018MeasuringSC,

title={Measuring semantic coherence of a conversation},

author={Svitlana Vakulenko and Maarten de Rijke and Michael Cochez and Vadim Savenkov and Axel Polleres},

booktitle={The Semantic Web - {ISWC} 2018 - 17th International Semantic Web Conference, Monterey, California, USA, October 8-12th, 2018, Proceedings},

year={2018}

}

Acknowledgments

This research is a product of collaboration between the University of Amsterdam (UvA), Fraunhofer Institute in Sankt Augustin and WU Wien. I am grateful to all my co-authors for the valuable inputs, which enabled this publication.

This work was supported by the following projects: EU H2020 program under the MSCA-RISE agreement 645751 (RISE_BPM), project Open Data for Local Communities funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Transport, Innovation and Technology (BMVIT) under the program “ICT of the Future“, between November 2016 and April 2019. More information https://iktderzukunft.at/en/

blog comments powered by Disqus