QRFA: A Data-Driven Model of Information Seeking Dialogues

ECIR 2019

Imagine conversation as a ``token game’’, where token is like a ping-pong ball that keeps bouncing in-between the players from one side to the other as they switch turns. Each player can either take the initiative with a pro-active move (attack) or reply to the maneuvre suggested by the opponent with a re-active move (defence). Advanced players can also perform both moves in a single turn, i.e. receive the ball and initiate the new attack within the same maneuvre. Let’s see an example of how such a ping-pong dialogue could sound like:

- Hello! How are you today? (pro-active action)

- Good, thank you! (re-active action)

- Let’s play ping-pong. (pro-active action)

- Sure. Do you have the rackets? (re-active + pro-active actions)

Such an example of a regular daily conversation illustrates the applicability of the ping-pong metaphor to the general conversational settings, in which each participant assumes an equal role in the conversation. However, it can be also used to describe other kinds of real-world conversations, and in particular the information-seeking conversations, which occur in the customer-service scenarios, such as library and shopping assistance services. In this type of dialogues the roles of the conversation participants are not symetric. One of the participants is regarded as the principal information seeker, while the other one is the principal information provider, who is there to help the seeker to satisfy the information need (Answer the Question). The key, however, is that the conversation participants can switch roles in the process of the conversation, when the information provider can Request additional information from the seeker to better understand the information need, and the seeker can provide intermediate Feedback to the provider as a support.

Problem Statement

The widespread use of conversational interfaces, such as personal assistants or voice control in self-driving cars, demands efficient tools for designing, monitoring and evaluation of dialog systems. Developers of dialogue systems require the means to:

- analyse the scope and the structure of the interactions the dialogue system should support, such as user intents and relations between them, to understand the system requirements;

- design the system components and the functions they need to support;

- collect relevant conversational data for training the dialogue system and ensure its quality, e.g. sample and preprocess;

- detect failures from the conversation transcripts to continuously improve the dialogue system.

Conversation Mining

We define conversation mining as process mining applied to conversation transcripts. Consider every dialogue to be an instance of a general conversation process unfolding in time. To understand the dynamics of the conversation process (rules of the game + a set of strategies the players employ) we analyse frequent patterns in dialogues represented as sequences of dialogue acts. Below is an example of a dialogue tree constructed from several restaurant reservation dialogues from the DSTC2 dataset:

At first glance, the dialogues seem very diverse due to the variance in natural language expressions but at a closer look every dialogue follows a very similar structural pattern, which becomes more apparent once we annotate the utterances with the abstract-level QRFA tags. Each dialogue begins with several turns identifying the information need of the seeker (RQR) and progresses towards question-answering (QAQ) and answer-refinement (AFA) subroutines.

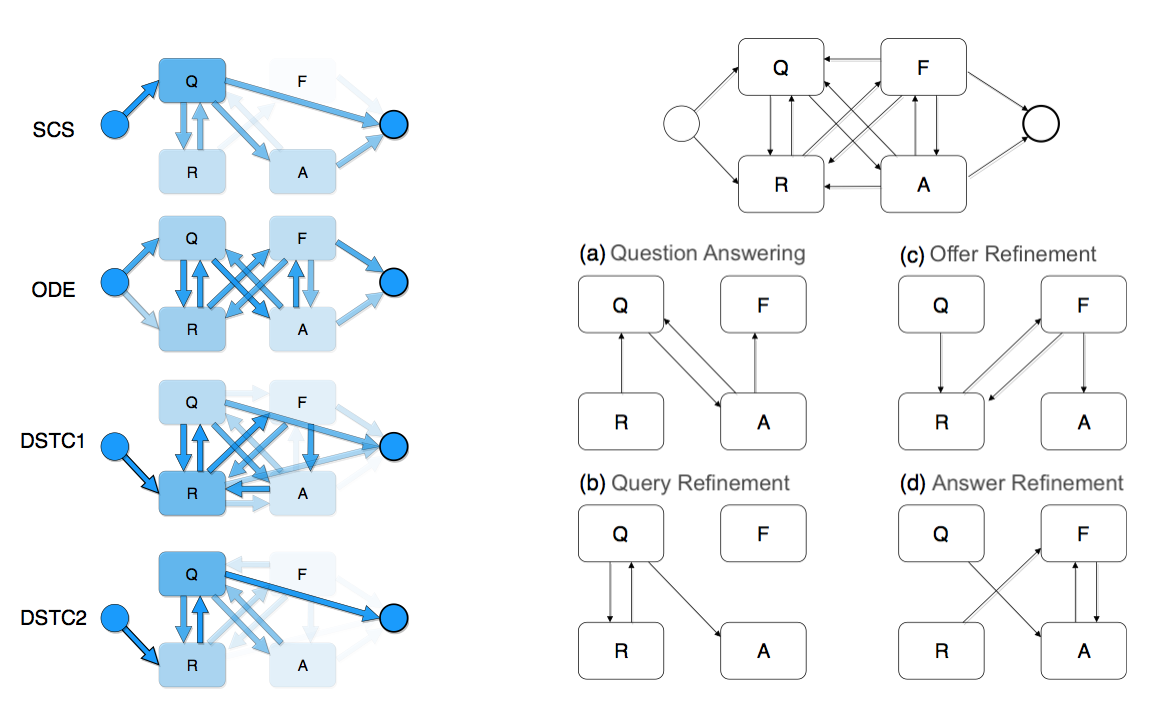

We analysed four dataset of information-seeking dialogues across different domains and extracted a general model using the QRFA annotation schema. First, four models were extracted from each of the datasets separately: Spoken Conversational Search (SCS), Open Data Exploration (ODE), Dialogue State Tracking challenge (DSTC1 and DSTC2).

The final QRFA model (on the right) is produced as a sum of the individual model graphs (model “as-is”) minus the edges, which represent transitions considered as undesirable for a conversation success (model “to-be”), e.g. Q->END transition was removed. This set of edges can be identified by a human analyst from the model without having to look through the individual dialogue transcript. The conversation model helps to formulate a hypothesis that can be then verified by sampling from only those dialogues, which contain the transition or a more complex pattern.

Discussion

Why does this matter? Process mining and other frequent pattern mining approaches provide an efficient mechanism able to extract interpretable models that can be traced back to the original observations in the dataset. This is important for developing grounded theories that can provide understanding of the problem space and enable model development with human-in-the-loop.

What are the challenges? There are no established standards for annotating information-seeking dialogues. Previously proposed annotation guidelines, such as the dialogue act labels introduced in the SWBD-DAMSL standard, do not meet the needs for the type of analysis required to design conversational search interfaces. It is not clear which features need to be encoded and what the granularity of the label set should be to aid analysis of conversational datasets and design of dialogue systems. As a result, every conversational dataset uses a different set of labels, which hinders reusability and integration of findings across individual use cases.

Find out more

For details of the approach that we used to extract the process model from the conversational transcripts and the model evaluation in terms of fitness, generalisation ability and dialogue break-down detection read our article that was accepted to ECIR 2019 as a full research paper (presentation in the Session 7a: “QA & Conversational Search” on Wednesday 17 April at 10:50AM in Maternussaal, Cologne, Germany).

Code: https://github.com/svakulenk0/conversation_mining

Slides: https://github.com/svakulenk0/svakulenk0.github.io/blob/master/pdfs/slides/ecir19.pdf

Reference

Svitlana Vakulenko, Kate Revoredo, Claudio Di Ciccio and Maarten de Rijke. QRFA: A Data-Driven Model of Information Seeking Dialogues. In Proceedings of the 41st European Conference on IR Research (ECIR 2019), Cologne, Germany, April 2019.

@InProceedings{10.1007/978-3-030-15712-8_35,

author="Vakulenko, Svitlana

and Revoredo, Kate

and Di Ciccio, Claudio

and de Rijke, Maarten",

title={QRFA: A Data-Driven Model of Information Seeking Dialogues},

booktitle="Advances in Information Retrieval",

year="2019",

publisher="Springer International Publishing",

pages="541--557",

isbn="978-3-030-15712-8"

}

Acknowledgments

This research is a product of collaboration between the University of Amsterdam, University of Rio and Vienna University of Economics and Business. I am grateful to all my co-authors for the valuable inputs, which made this publication possible.

This work was supported by the following projects: EU H2020 program under the MSCA-RISE agreement 645751 (RISE_BPM), project Open Data for Local Communities funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Transport, Innovation and Technology (BMVIT) under the program “ICT of the Future“, between November 2016 and April 2019. More information https://iktderzukunft.at/en/

blog comments powered by Disqus